a écrit :The Flagellum Unspun

The Collapse of "Irreducible Complexity"

Kenneth R. Miller

Brown University

Providence, Rhode Island

This is a pre-publication copy of an article that will appear in volume entitled "Debating Design: from Darwin to DNA," edited by Michael Ruse and William Dembski, which will be published by Cambridge University Press volume in 2004. I will provide exact citation information for the article when the volume is published.

Almost from the moment The Origin of Species was published in 1859, the opponents of evolution have fought a long, losing battle against their Darwinian foes. Today, like a prizefighter in the late rounds losing badly on points, they've placed their hopes in one big punch – a single claim that might smash through the overwhelming weight of scientific evidence to bring Darwin to the canvas once and for all. Their name for this virtual roundhouse right is "intelligent design."

In the last several years, the intelligent design movement has attempted to move against science education standards in several American states, most famously in Kansas and Ohio (Holden 1999; Gura 2002). The principal claim made by adherents of this view is that they can detect the presence of "intelligent design" in complex biological systems. As evidence, they cite a number of specific examples, including the vertebrate blood clotting cascade, the eukaryotic cilium, and most notably, the eubacterial flagellum (Behe 1996a, Behe 2002).

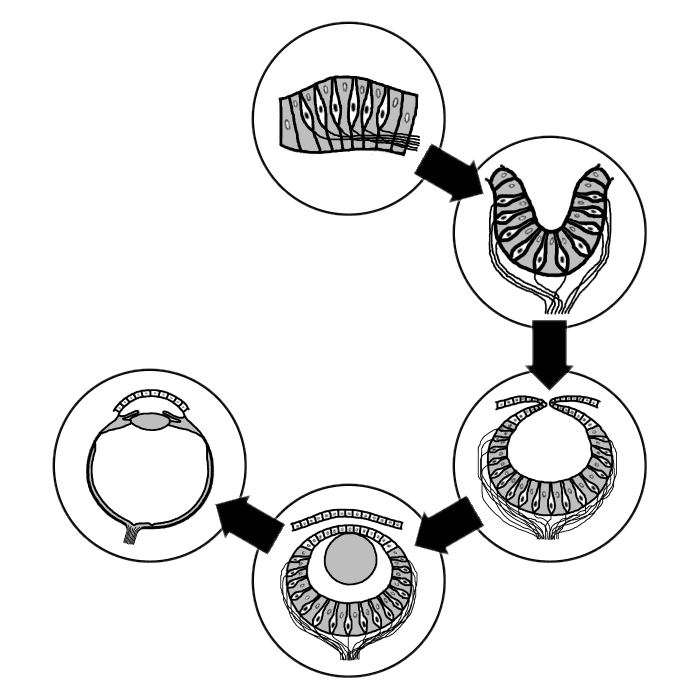

Of all these examples, the flagellum has been presented so often as a counter-example to evolution that it might well be considered the "poster child" of the modern anti-evolution movement. Variations of its image (Figure 1) now appear on web pages of anti-evolution groups like the Discovery Institute, and on the covers of "intelligent design" books such as William Dembski's No Free Lunch (Dembski 2002a). To anti-evolutionists, the high status of the flagellum reflects the supposed fact that it could not possibly have been produced by an evolutionary pathway.

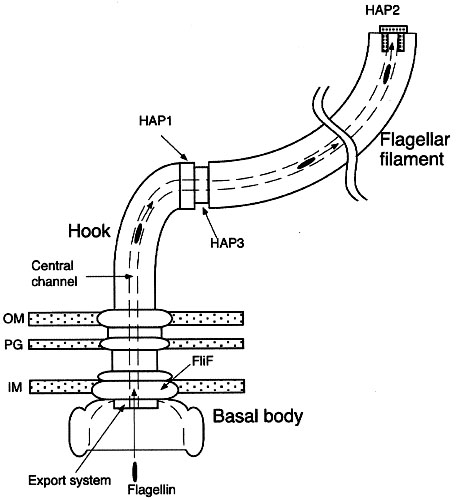

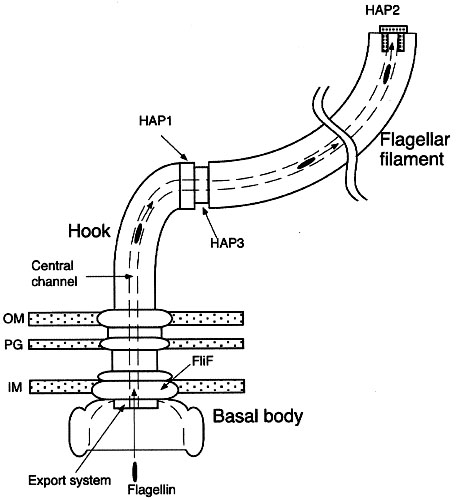

Figure 1: The eubacterial flagellum. The flagellum is an ion-powered rotary motor, anchored in the membranes surrounding the bacterial cell. This schematic diagram highlights the assembly process of the bacterial flagellar filament and the cap-filament complex. OM, outer membrane; PG, peptidoglycan layer; IM, cytoplasmic membrane (From Yonekura et al 2000).

Figure 1: The eubacterial flagellum. The flagellum is an ion-powered rotary motor, anchored in the membranes surrounding the bacterial cell. This schematic diagram highlights the assembly process of the bacterial flagellar filament and the cap-filament complex. OM, outer membrane; PG, peptidoglycan layer; IM, cytoplasmic membrane (From Yonekura et al 2000).There is, to be sure, nothing new or novel in an anti-evolutionist pointing to a complex or intricate natural structure, and professing skepticism that it could have been produced by the "random" processes of mutation and natural selection. Nonetheless, the "argument from personal incredulity," as such sentiment has been appropriately described, has been a weapon of little value in the anti-evolution movement. Anyone can state at any time that they cannot imagine how evolutionary mechanisms might have produced a certain species, organ, structure. Such statements, obviously, are personal – and they say more about the limitations of those who make them than they do about the limitations of Darwinian mechanisms.

The hallmark of the intelligent design movement, however, is that it purports to rise above the level of personal skepticism. It claims to have found a reason why evolution could not have produced a structure like the bacterial flagellum, a reason based on sound, solid scientific evidence.

Why does the intelligent design movement regard the flagellum as unevolvable? Because it is said to possesses a quality known as "irreducible complexity." Irreducibly complex structures, we are told, could not have been produced by evolution, or, for that matter, by any natural process. They do exist, however, and therefore they must have been produced by something. That something could only be an outside intelligent agency operating beyond the laws of nature – an intelligent designer. That, simply stated, is the core of the new argument from design, and the intellectual basis of the intelligent design movement.

The great irony of the flagellum's increasing acceptance as an icon of anti-evolution is that fact that research had demolished its status as an example of irreducible complexity almost at the very moment it was first proclaimed. The purpose of this article is to explore the arguments by which the flagellum's notoriety has been achieved, and to review the research developments that have now undermined they very foundations of those arguments.

The Argument's OriginsThe flagellum owes its status principally to Darwin's Black Box (Behe 1996a) a book by Michael Behe that employed it in a carefully-crafted anti-evolution argument. Building upon William Paley's well-known "argument from design," Behe sought to bring the argument two centuries forward into the realm of biochemistry. Like Paley, Behe appealed to his readers to appreciate the intricate complexity of living organisms as evidence for the work of a designer. Unlike Paley, however, he raised the argument to a new level, claiming to have discovered a scientific principle that could be used to prove that certain structures could not have been produced by evolution. That principle goes by the name of "irreducible complexity."

An irreducibly complex structure is defined as ". . . a single system composed of several well-matched, interacting parts that contribute to the basic function, wherein the removal of any one of the parts causes the system to effectively cease functioning." (Behe 1996a, 39) Why would such systems present difficulties for Darwinism? Because they could not possibly have been produced by the process of evolution:

"An irreducibly complex system cannot be produced directly by numerous, successive, slight modifications of a precursor system, because any precursor to an irreducibly complex system that is missing a part is by definition nonfunctional. .... Since natural selection can only choose systems that are already working, then if a biological system cannot be produced gradually it would have to arise as an integrated unit, in one fell swoop, for natural selection to have anything to act on." (Behe 1996b)

The phrase "numerous, successive, slight modifications" is not accidental. The very same words were used by Charles Darwin in The Origin of Species in describing the conditions that had to be met for his theory to be true. As Darwin wrote, if one could find an organ or structure that could not have been formed by "numerous, successive, slight modifications," his "theory would absolutely break down" (Darwin 1859, 191). To anti-evolutionists, the bacterial flagellum is now regarded as exactly such a case – an "irreducibly complex system" which "cannot be produced directly by numerous successive, slight modifications." A system that could not have evolved – a desperation punch that just might win the fight in the final round – a tool with which the theory of evolution can be brought down.

The Logic of Irreducible ComplexityLiving cells are filled, of course, with complex structures whose detailed evolutionary origins are not known. Therefore, in fashioning an argument against evolution one might pick nearly any cellular structure, the ribosome for example, and claim – correctly – that its origin has not been explained in detail by evolution.

Such arguments are easy to make, of course, but nature of scientific progress renders them far from compelling. The lack of a detailed current explanation for a structure, organ, or process does not mean that science will never come up with one. As an example, one might consider the question of how left-right asymmetry arises in vertebrate development, a question that was beyond explanation until the 1990s (Belmonte 1999). In 1990 one might have argued that the body's left-right asymmetry could just as well be explained by the intervention of a designer as by an unknown molecular mechanism. Only a decade later, the actual molecular mechanism was identified (Stern 2002), and any claim one might have made for the intervention of a designer would have been discarded. The same point can be made, of course, regarding any structure or mechanism whose origins are not yet understood.

The utility of the bacterial flagellum is that it seems to rise above this "argument from ignorance." By asserting that it is a structure "in which the removal of an element would cause the whole system to cease functioning" (Behe 2002), the flagellum is presented as a "molecular machine" whose individual parts must have been specifically crafted to work as a unified assembly. The existence of such a multipart machine therefore provides genuine scientific proof of the actions of an intelligent designer.

In the case of the flagellum, the assertion of irreducible complexity means that a minimum number of protein components, perhaps 30, are required to produce a working biological function. By the logic of irreducible complexity, these individual components should have no function until all 30 are put into place, at which point the function of motility appears. What this means, of course, is that evolution could not have fashioned those components a few at a time, since they do not have functions that could be favored by natural selection. As Behe wrote: " . . . natural selection can only choose among systems that are already working" (Behe 2002), and an irreducibly complex system does not work unless all of its parts are in place. The flagellum is irreducibly complex, and therefore, it must have been designed. Case closed.

Answering the ArgumentThe assertion that cellular machines are irreducibly complex, and therefore provide proof of design, has not gone unnoticed by the scientific community. A number of detailed rebuttals have appeared in the literature, and many have pointed out the poor reasoning of recasting the classic argument from design in the modern language of biochemistry (Coyne 1996; Miller 1996; Depew 1998; Thornhill and Ussery 2000). I have suggested elsewhere that the scientific literature contains counter-examples to any assertion that evolution cannot explain biochemical complexity (Miller 1999, 147), and other workers have addressed the issue of how evolutionary mechanisms allow biological systems to increase in information content (Schneider 2000; Adami, Ofria, and Collier 2000).

The most powerful rebuttals to the flagellum story, however, have not come from direct attempts to answer the critics of evolution. Rather, they have emerged from the steady progress of scientific work on the genes and proteins associated with the flagellum and other cellular structures. Such studies have now established that the entire premise by which this molecular machine has been advanced as an argument against evolution is wrong – the bacterial flagellum is not irreducibly complex. As we will see, the flagellum – the supreme example of the power of this new "science of design" – has failed its most basic scientific test. Remember the claim that "any precursor to an irreducibly complex system that is missing a part is by definition nonfunctional?" As the evidence has shown, nature is filled with examples of "precursors" to the flagellum that are indeed "missing a part," and yet are fully-functional. Functional enough, in some cases, to pose a serious threat to human life.

The Type -III Secretory ApparatusIn the popular imagination, bacteria are "germs" – tiny microscopic bugs that make us sick. Microbiologists smile at that generalization, knowing that most bacteria are perfectly benign, and many are beneficial – even essential – to human life. Nonetheless, there are indeed bacteria that produce diseases, ranging from the mildly unpleasant to the truly dangerous. Pathogenic, or disease-causing, bacteria threaten the organisms they infect in a variety of ways, one of which is to produce poisons and inject them directly into the cells of the body. Once inside, these toxins break down and destroy the host cells, producing illness, tissue damage, and sometimes even death.

In order to carry out this diabolical work, bacteria must not only produce the protein toxins that bring about the demise of their hosts, but they must efficiently inject them across the cell membranes and into the cells of their hosts. They do this by means of any number of specialized protein secretory systems. One, known as the type III secretory system (TTSS), allows gram negative bacteria to translocate proteins directly into the cytoplasm of a host cell (Heuck 1998). The proteins transferred through the TTSS include a variety of truly dangerous molecules, some of which are known as "virulence factors," and are directly responsible for the pathogenic activity of some of the most deadly bacteria in existence (Büttner and Bonas 2002; Heuck 1998).

At first glance, the existence of the TTSS, a nasty little device that allows bacteria to inject these toxins through the cell membranes of its unsuspecting hosts, would seem to have little to do with the flagellum. However, molecular studies of proteins in the TTSS have revealed a surprising fact – the proteins of the TTSS are directly homologous to the proteins in the basal portion of the bacterial flagellum. As figure 2 (Heuck 1998) shows, these homologies extend to a cluster of closely-associated proteins found in both of these molecular "machines." On the basis of these homologies, McNab (McNab 1999) has argued that the flagellum itself should be regarded as a type III secretory system. Extending such studies with a detailed comparison of the proteins associated with both systems, Aizawa has seconded this suggestion, noting that the two systems "consist of homologous component proteins with common physico-chemical properties" (Aizawa 2001, 163). It is now clear, therefore, that a smaller subset of the full complement of proteins in the flagellum makes up the functional transmembrane portion of the TTSS.

Figure 2: There are extensive homologies between type III secretory proteins and proteins involved in export in the basal region of the bacterial flagellum. These homologies demonstrate that the bacterial flagellum is not "irreducibly complex." In this diagram (redrawn from Heuck 1998), the shaded portions of the basal region indicate proteins in the E. coli flagellum homologous to the Type III secretory structure of Yersinia. . OM, outer membrane; PP, periplasmic space; CM, cytoplasmic membrane.

Figure 2: There are extensive homologies between type III secretory proteins and proteins involved in export in the basal region of the bacterial flagellum. These homologies demonstrate that the bacterial flagellum is not "irreducibly complex." In this diagram (redrawn from Heuck 1998), the shaded portions of the basal region indicate proteins in the E. coli flagellum homologous to the Type III secretory structure of Yersinia. . OM, outer membrane; PP, periplasmic space; CM, cytoplasmic membrane. Stated directly, the TTSS does its dirty work using a handful of proteins from the base of the flagellum. From the evolutionary point of view, this relationship is hardly surprising. In fact, it's to be expected that the opportunism of evolutionary processes would mix and match proteins to produce new and novel functions. According to the doctrine of irreducible complexity, however, this should not be possible. If the flagellum is indeed irreducibly complex, then removing just one part, let alone 10 or 15, should render what remains "by definition nonfunctional." Yet the TTSS is indeed fully-functional, even though it is missing most of the parts of the flagellum. The TTSS may be bad news for us, but for the bacteria that possess it, it is a truly valuable biochemical machine.

The existence of the TTSS in a wide variety of bacteria demonstrates that a small portion of the "irreducibly complex" flagellum can indeed carry out an important biological function. Since such a function is clearly favored by natural selection, the contention that the flagellum must be fully-assembled before any of its component parts can be useful is obviously incorrect. What this means is that the argument for intelligent design of the flagellum has failed.

CounterattackClassically, one of the most widely-repeated charges made by anti-evolutionists is that the fossil record contains wide "gaps" for which transitional fossils have never been found. Therefore, the intervention of a creative agency, an intelligent designer, must be invoked to account for each gap. Such gaps, of course, have been filled with increasing frequency by paleontologists – the increasingly rich fossil sequences demonstrating the origins of whales are a useful examples (Thewissen, Hussain, and Arif 1994; Thewissen, Williams, Roe, and Hussain 2001). Ironically, the response of anti-evolutionists to such discoveries is frequently to claim that things have only gotten worse for evolution. Where previously there had been just one gap, as a result of the transitional fossil, now there are two (one on either side of the newly-discovered specimen).

As word of the relationship between the eubacterial flagellum and the TTSS has begun to spread among the "design" community, the first hints of a remarkably similar reaction have emerged. The TTSS only makes problems worse for evolution, according to this response, because now there are two irreducibly-complex systems to deal with. The flagellum is still irreducibly complex – but so is the TTSS. But now there are two systems for evolutionists to explain instead of just one.

Unfortunately for this line of argument, the claim that one irreducibly-complex system might contain another is self-contradictory. To understand this, we need to remember that the entire point of the design argument, as exemplified by the flagellum, is that only the entire biochemical machine, with all of its parts, is functional. For the intelligent design argument to stand, this must be the case, since it provides the basis for their claim that only the complete flagellum can be favored by natural selection, not any its component parts.

However, if the flagellum contains within it a smaller functional set of components like the TTSS, then the flagellum itself cannot be irreducibly complex – by definition. Since we now know that this is indeed the case, it is obviously true that the flagellum is not irreducibly complex.

A second reaction, which I have heard directly after describing the relationship between the secretory apparatus and the flagellum, is the objection that the TTSS does not tell us how either it or the flagellum evolved. This is certainly true, although Aizawa has suggested that the TTSS may indeed be an evolutionary precursor of the flagellum (Aizawa 2001). Nonetheless, until we have produced a step-by-step account for the evolutionary derivation of the flagellum, one may indeed invoke the argument from ignorance for this and every other complex biochemical machine.

However, in agreeing to this, one must keep in mind that the doctrine of irreducible complexity was intended to go one step beyond the claim of ignorance. It was fashioned in order to provide a rationale for claiming that the bacterial flagellum couldn't have evolved, even in principle, because it is irreducibly complex. Now that a simpler, functional system (the TTSS) has been discovered among the protein components of the flagellum, the claim of irreducible complexity has collapsed, and with it any "evidence" that the flagellum was designed.

Combinatorial ArgumentAt first glance, William Dembski's case for intelligent design seems to follow a distinctly different strategy in dealing with biological complexity. His recent book, No Free Lunch (Dembski 2002a), lays out this case, using information theory and mathematics to show that life is the result of intelligent design. Dembski makes the assertion that living organisms contain what he calls "complex specified information" (CSI), and claims to have shown that the evolutionary mechanism of natural selection cannot produce CSI. Therefore, any instance of CSI in a living organism must be the result of intelligent design. And living organisms, according to Dembski, are chock-full of CSI.

Dembski's arguments, couched in the language of information theory, are highly technical and are defended, almost exclusively, by reference to their utility in detecting information produced by human beings. These include phone and credit card numbers, symphonies, and artistic woodcuts, to name just a few. One might then expect that Dembski, having shown how the presence of CSI can be demonstrated in man made objects, would then turn to a variety of biological objects. Instead, he turns to just one such object, the bacterial flagellum.

Dembski then offers his readers a calculation showing that the flagellum could not have possibly have evolved. Significantly, he begins that calculation by linking his arguments to those of Behe, writing: "I want therefore in this section to show how irreducible complexity is a special case of specified complexity, and in particular I want to sketch how one calculates the relevant probabilities needed to eliminate chance and infer design for such systems" (Dembski 2002a, 289). Dembski then tells us that an irreducibly complex system, like the flagellum, is a "discrete combinatorial object." What this means, as he explains, is that the probability of assembling such an object can be calculated by determining the probabilities that each of its components might have originated by chance, that they might have been localized to the same region of the cell, and that they would be assembled in precisely the right order. Dembski refers to these three probabilities as Porig, Plocal, and Pconfig, and he regards each of them as separate and independent (Dembski 2002a, 291).

This approach overlooks the fact that the last two probabilities are actually contained within the first. Localization and self-assembly of complex protein structures in prokaryotic cells are properties generally determined by signals built into the primary structures of the proteins themselves. The same is likely true for the amino acid sequences of the 30 or so protein components of the flagellum and the approximately 20 proteins involved in the flagellum's assembly (McNab 1999; Yonekura et al 2000). Therefore, if one gets the sequences of all the proteins right, localization and assembly will take care of themselves.

To the ID enthusiast, however, this is a point of little concern. According to Dembski, evolution could still not construct the 30 proteins needed for the flagellum. His reason is that the probability of their assembly falls below what he terms the "universal probability bound." According to Dembski, the probability bound is a sensible allowance for the fact that highly improbable events do occur from time to time in nature. To allow for such events, he agrees that given enough time, any event with a probability larger than 10-150 might well take place. Therefore, if a sequence of events, such as a presumed evolutionary pathway, has a calculated probability less than 10-150 , we may conclude that the pathway is impossible. If the calculated probability is greater than 10-150, it's possible (even if unlikely).

When Dembski turns his attention to the chances of evolving the 30 proteins of the bacterial flagellum, he makes what he regards as a generous assumption. Guessing that each of the proteins of the flagellum have about 300 amino acids, one might calculate that the chances of getting just one such protein to assemble from "random" evolutionary processes would be 20-300 , since there are 20 amino acids specified by the genetic code. Dembski, however, concedes that proteins need not get the exact amino acid sequence right in order to be functional, so he cuts the odds to just 20-30, which he tells his readers is "on the order of 10-39" (Dembski 2002a, 301). Since the flagellum requires 30 such proteins, he explains that 30 such probabilities "will all need to be multiplied to form the origination probability"(Dembski 2002a, 301). That would give us an origination probability for the flagellum of 10 -1170, far below the universal probability bound. The flagellum couldn't have evolved, and now we have the numbers to prove it. Right?

Assuming ImpossibilityI have no doubt that to the casual reader, a quick glance over the pages of numbers and symbols in Dembski's books is impressive, if not downright intimidating. Nonetheless, the way in which he calculates the probability of an evolutionary origin for the flagellum shows how little biology actually stands behind those numbers. His computation calculates only the probability of spontaneous, random assembly for each of the proteins of the flagellum. Having come up with a probability value on the order of 10 -1170, he assures us that he has shown the flagellum to be unevolvable. This conclusion, of course, fits comfortably with his view is that "The Darwinian mechanism is powerless to produce irreducibly complex systems..." (Dembski 2002a, 289).

However complex Dembski's analysis, the scientific problem with his calculations is almost too easy to spot. By treating the flagellum as a "discrete combinatorial object" he has shown only that it is unlikely that the parts flagellum could assemble spontaneously. Unfortunately for his argument, no scientist has ever proposed that the flagellum or any other complex object evolved that way. Dembski, therefore, has constructed a classic "straw man" and blown it away with an irrelevant calculation.

By treating the flagellum as a discrete combinatorial object he has assumed in his calculation that no subset of the 30 or so proteins of the flagellum could have biological activity. As we have already seen, this is wrong. Nearly a third of those proteins are closely related to components of the TTSS, which does indeed have biological activity. A calculation that ignores that fact has no scientific validity.

More importantly, Dembski's willingness to ignore the TTSS lays bare the underlying assumption of his entire approach towards the calculation of probabilities and the detection of "design." He assumes what he is trying to prove.

According to Dembski, the detection of "design" requires that an object display complexity that could not be produced by what he calls "natural causes." In order to do that, one must first examine all of the possibilities by which an object, like the flagellum, might have been generated naturally. Dembski and Behe, of course, come to the conclusion that there are no such natural causes. But how did they determine that? What is the scientific method used to support such a conclusion? Could it be that their assertions of the lack of natural causes simply amount to an unsupported personal belief? Suppose that there are such causes, but they simply happened not to think of them? Dembski actually seems to realize that this is a serious problem. He writes: "Now it can happen that we may not know enough to determine all the relevant chance hypotheses [which here, as noted above, means all relevant natural processes (hvt)]. Alternatively, we might think we know the relevant chance hypotheses, but later discover that we missed a crucial one. In the one case a design inference could not even get going; in the other, it would be mistaken" (Dembski 2002, 123 (note 80)).

What Dembski is telling us is that in order to "detect" design in a biological object one must first come to the conclusion that the object could not have been produced by any "relevant chance hypotheses" (meaning, naturally, evolution). Then, and only then, are Dembski's calculations brought into play. Stated more bluntly, what this really means is that the "method" first involves assuming the absence of an evolutionary pathway leading to the object, followed by a calculation "proving" the impossibility of spontaneous assembly. Incredibly, this a priori reasoning is exactly the sort of logic upon which the new "science of design" has been constructed.

Not surprisingly, scientific reviewers have not missed this point – Dembski's arguments have been repeatedly criticized on this issue and on many others (Orr 2002; Charlesworth 2002; Padian 2002).

Designing the CycleIn assessing the design argument, therefore, it only seems as though two distinct arguments have been raised for the unevolvability of the flagellum. In reality, those two arguments, one invoking irreducible complexity and the other specified complex information, both depend upon a single scientifically insupportable position. Namely, that we can look at a complex biological object and determine with absolute certainty that none of its component parts could have been first selected to perform other functions. The discovery of extensive homologies between the Type III secretory system and the flagellum has now shown just how wrong that position was.

When anti-evolutionary arguments featuring the bacterial flagellum rose into prominence, beginning with the 1996 publication of Darwin's Black Box (Behe 1996a), they were predicated upon the assertion that each of the protein components of the flagellum were crafted, in a single act of design, to fit the specific purpose of the flagellum. The flagellum was said to be unevolvable since the entire complex system had to be assembled first in order to produce any selectable biological function. This claim was broadened to include all complex biological systems, and asserted further that science would never find an evolutionary pathway to any of these systems. After all, it hadn't so far, at least according to one of "design's" principal advocates:

There is no publication in the scientific literature – in prestigious journals, specialty journals, or books – that describes how molecular evolution of any real, complex, biochemical system either did occur or even might have occurred. (Behe 1996a, 185)

As many critics of intelligent design have pointed out, that statement is simply false. Consider, as just one example, the Krebs cycle, an intricate biochemical pathway consisting of nine enzymes and a number of cofactors that occupies center stage in the pathways of cellular metabolism. The Krebs cycle is "real," "complex," and "biochemical." Does it also present a problem for evolution? Apparently yes, according to the authors of a 1996 paper in the Journal of Molecular evolution, who wrote:

"The Krebs cycle has been frequently quoted as a key problem in the evolution of living cells, hard to explain by Darwin’s natural selection: How could natural selection explain the building of a complicated structure in toto, when the intermediate stages have no obvious fitness functionality? (Melendez-Hevia, Wadell, and Cascante 1996)

Where intelligent design theorists throw up their hands and declare defeat for evolution, however, these researchers decided to do the hard scientific work of analyzing the components of the cycle, and seeing if any of them might have been selected for other biochemical tasks. What they found should be a lesson to anyone who asserts that evolution can only act by direct selection for a final function. In fact, nearly all of the proteins of the complex cycle can serve different biochemical purposes within the cell, making it possible to explain in detail how they evolved:

In the Krebs cycle problem the intermediary stages were also useful, but for different purposes, and, therefore, its complete design was a very clear case of opportunism. . . . the Krebs cycle was built through the process that Jacob (1977) called ‘‘evolution by molecular tinkering,’’ stating that evolution does not produce novelties from scratch: It works on what already exists. The most novel result of our analysis is seeing how, with minimal new material, evolution created the most important pathway of metabolism, achieving the best chemically possible design. In this case, a chemical engineer who was looking for the best design of the process could not have found a better design than the cycle which works in living cells." (Melendez-Hevia, Wadell, and Cascante 1996)

Since this paper appeared, a study based on genomic DNA sequences has confirmed the validity of this approach (Huynen, Dandekar, and Bork 1999). By contrast, how would intelligent design have approached the Krebs Cycle? Using Dembski's calculations as our guide, we would first determine the amino acid sequences of each of the proteins of the cycle, and then calculate the probability of their spontaneous assembly. When this is done, an origination probability of less than 10 -400 is the result. Therefore, the result of applying "design" as a predictive science would have told both groups of researchers that their ultimately successful studies would have been fruitless, since the probability of spontaneous assembly falls below the "universal probability bound."

We already know, however, the reason that such calculations fail. They carry a built-in assumption that the component parts of a complex biochemical system have no possible functions beyond the completely assembled system itself. As we have seen, this assumption is false. The Krebs cycle researchers knew better, of course, and were able to produce two important studies describing how a real, complex, biochemical system might have evolved – the very thing that design theorists once claimed did not exist in the scientific literature.

The Failure of DesignIt is no secret that concepts like "irreducible complexity" and "intelligent design" have failed to take the scientific community by storm (Forrest 2002). Design has not prompted new research studies, new breakthroughs, or novel insights on so much as a single scientific question. Design advocates acknowledge this from time to time, but they often claim that this is because the scientific deck is stacked against them. The Darwinist establishment, they say, prevents them from getting a foot in the laboratory door.

I would suggest that the real reason for the cold shoulder given "design" by the scientific community, particularly by life science researchers, is because time and time again its principal scientific claims have turned out to be wrong. Science is a pragmatic activity, and if your hypothesis doesn't work, it is quickly discarded.

The claim of irreducible complexity for the bacterial flagellum is an obvious example of this, but there are many others. Consider, for example, the intricate cascade of proteins involved in the clotting of vertebrate blood. This has been cited as one of the principal examples of the kind of complexity that evolution cannot generate, despite the elegant work of Russell Doolittle (Doolittle and Feng 1987; Doolittle 1993) to the contrary. A number of proteins are involved in this complex pathway, as described by Behe:

When an animal is cut, a protein called Hagemann factor (XII) sticks to the surface of cells near the wound. Bound Hagemann factor is then cleaved by a protein called HMK to yield activated Hagemann factor. Immediately the activated Hagemann factor converts another protein, called prekallikrein, to its active form, kallikrein. (Behe 1996a, 84)

How important are each of these proteins? In line with the dogma of irreducible complexity, Behe argues that each and every component must be in place before the system will work, and he is perfectly clear on this point:

. . . none of the cascade proteins are used for anything except controlling the formation of a clot. Yet in the absence of any of the components, blood does not clot, and the system fails. (Behe 1996a, 86)

As we have seen, the claim that every one of the components must be present for clotting to work is central to the "evidence" for design. One of those components, as these quotations indicate, is Factor XII, which initiates the cascade. Once again, however, a nasty little fact gets in the way of intelligent design theory. Dolphins lack Factor XII (Robinson, Kasting, and Aggeler 1969), and yet their blood clots perfectly well. How can this be if the clotting cascade is indeed irreducibly complex? It cannot, of course, and therefore the claim of irreducible complexity is wrong for this system as well. I would suggest, therefore, that the real reason for the rejection of "design" by the scientific community is remarkably simple – the claims of the intelligent design movement are contradicted time and time again by the scientific evidence.

The Flagellum UnspunIn any discussion of the question of "intelligent design," it is absolutely essential to determine what is meant by the term itself. If, for example, the advocates of design wish to suggest that the intricacies of nature, life, and the universe reveal a world of meaning and purpose consistent with an overarching, possibly Divine intelligence, then their point is philosophical, not scientific. It is a philosophical point of view, incidentally, that I share, along with many scientists. As H. Allen Orr pointed out in a recent review:

Plenty of scientists have, after all, been attracted to the notion that natural laws reflect (in some way that's necessarily poorly articulated) an intelligence or aesthetic sensibility. This is the religion of Einstein, who spoke of "the grandeur of reason incarnate in existence" and of the scientist's "religious feeling [that] takes the form of a rapturous amazement at the harmony of natural law." (Orr 2002).

This, however, is not what is meant by "intelligent design" in the parlance of the new anti-evolutionists. Their views demand not a universe in which the beauty and harmony of natural law has brought a world of vibrant and fruitful life into existence, but rather a universe in which the emergence and evolution of life is made expressly impossible by the very same rules. Their view requires that the source of each and every novelty of life was the direct and active involvement of an outside designer whose work violated the very laws of nature he had fashioned. The world of intelligent design is not the bright and innovative world of life that we have come to know through science. Rather, it is a brittle and unchanging landscape, frozen in form and unable to adapt except at the whims of its designer.

Certainly, the issue of design and purpose in nature is a philosophical one that scientists can and should discuss with great vigor. However, the notion at the heart's of today intelligent design movement is that the direct intervention of an outside designer can be demonstrated by the very existence of complex biochemical systems. What even they acknowledge is that their entire scientific position rests upon a single assertion – that the living cell contains biochemical machines that are irreducibly complex. And the bacterial flagellum is the prime example of such a machine.

Such an assertion, as we have seen, can be put to the test in a very direct way. If we are able to search and find an example of a machine with fewer protein parts, contained within the flagellum, that serves a purpose distinct from motility, the claim of irreducible complexity is refuted. As we have also seen, the flagellum does indeed contain such a machine, a protein-secreting apparatus that carries out an important function even in species that lack the flagellum altogether. A scientific idea rises or falls on the weight of the evidence, and the evidence in the case of the bacterial flagellum is abundantly clear.

As an icon of anti-evolution, the flagellum has fallen. The very existence of the Type III Secretory System shows that the bacterial flagellum is not irreducibly complex. It also demonstrates, more generally, that the claim of "irreducible complexity" is scientifically meaningless, constructed as it is upon the flimsiest of foundations – the assertion that because science has not yet found selectable functions for the components of a certain structure, it never will. In the final analysis, as the claims of intelligent design fall by the wayside, its advocates are left with a single, remaining tool with which to battle against the rising tide of scientific evidence. That tool may be effective in some circles, of course, but the scientific community will be quick to recognize it for what it really is – the classic argument from ignorance, dressed up in the shiny cloth of biochemistry and information theory.

When three leading advocates of intelligent design were recently given a chance to make their case in an issue of Natural History magazine, they each concluded their articles with a plea for design. One wrote that we should recognize "the design inherent in life and the universe" (Behe 2002), another that "design remains a possibility" (Wells 2002), and another "that the natural sciences need to leave room for design" (Dembski 2002b). Yes, it is true. Design does remain a possibility, but not the type of "intelligent design" of which they speak.

As Darwin wrote, there is grandeur in an evolutionary view of life, a grandeur that is there for all to see, regardless of their philosophical views on the meaning and purpose of life. I do not believe, even for an instant, that Darwin's vision has weakened or diminished the sense of wonder and awe that one should feel in confronting the magnificence and diversity of the living world. Rather, to a person of faith it should enhance their sense of the Creator's majesty and wisdom (Miller 1999). Against such a backdrop, the struggles of the intelligent design movement are best understood as clamorous and disappointing double failures – rejected by science because they do not fit the facts, and having failed religion because they think too little of God.

Bibliography

Adami, C., C. Ofria, and T. C. Collier, 2000. Evolution of biological complexity, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 97: 4463—4468.

Aizawa, S.-I., 2001. Bacterial flagella and type III secretion systems, FEMS Microbiology Letters 202: 157-164.

Behe, M, 1996b. Evidence for Intelligent Design from Biochemistry, a speech given at the Discovery Institute's God & Culture Conference, August 10, 1996 Seattle, WA. Available from World Wide Web:

http://www.arn.org/docs/behe/mb_idfrombiochemistry.htmBehe, M. 1996a. Darwin's Black Box. New York: The Free Press.

Behe, M., 2002. The challenge of irreducible complexity, Natural History 111 (April): 74.

Büttner D., and U. Bonas, 2002. Port of entry - the Type III secretion translocon, Trends in Microbiology 10: 186-191.

Belmonte, J. C. I. , 1999. How the body tells right from left. Scientific American 280 (June): 46-51.

Charlesworth, B., 2002. Evolution by Design? Nature 418: 129.

Coyne, J. A., 1996. God in the details, Nature 383: 227-228.

Darwin, C. 1872. The Origin of Species (6th edition). London: Oxford University Press.

Dembski, W. 2002a, No Free Lunch: Why specified complexity cannot be purchased without intelligence. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

Dembski, W., 2002b. Detecting design in the natural sciences, Natural History 111 (April): 76.

Depew, D. J. (1998), Intelligent design and irreducible complexity: A rejoinder. Rhetoric and Public Affairs 1: 571-578.

Doolittle, R. F., 1993. The evolution of vertebrate blood coagulation: A case of yin and yang, Thrombosis and Heamostasis 70: 24-28.

Doolittle, R. F., and D. F. Feng, 1987. Reconstructing the evolution of vertebrate blood coagulation from a consideration of the amino acid sequences of clotting proteins. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology 52: 869-874.

Forrest B., 2002. The newest evolution of creationism. Natural History 111 (April): 80.

Gura, T., 2002, Evolution Critics seek role for unseen hand in education. Nature 416: 250.

Heuck, C. J., 1998. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants, Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62: 379-433.

Holden, C., 1999. Kansas Dumps Darwin, Raises Alarm Across the United States. Science 285: 1186-1187.

Huynen, M. A., T. Dandekar, and P. Bork (1999) Variation and evolution of the citric-acid cycle: a genomic perspective. Trends in Microbiology 7: 281-291.

McNab, R. M., 1999. The Bacterial Flagellum: Reversible Rotary Propellor and Type III Export Apparatus. Journal of Bacteriology 181: 7149—7153.

Melendez-Hevia, E., T. G. Wadell, and M. Cascante, 1996. The puzzle of the Krebs citric acid cycle: Assembling the pieces of chemically feasible reactions, and opportunism in the design of metabolic pathways during evolution. J. Molecular Evolution 43: 293—303

Miller, K. R. 1999. Finding Darwin's God. New York: Harper Collins.

Miller, K. R., 1996. A review of Darwin's Black Box, Creation/Evolution 16: 36-40.

Orr, H. A., 2002. The Return of Intelligent Design, The Boston Review (Summer 2002 Issue).

Padian, K., 2002. Waiting for the Watchmaker, Science 295: 2373-2374.

Pennock, R. T., 2001. Intelligent Design Creationism and Its Critics: Philosophical, Theological, and Scientific Perspectives. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Robinson, A. J., M. Kropatkin, and P. M. Aggeler, 1969. Hagemann Factor (Factor XII) Deficiency in Marine Mammals. Science 166: 1420-1422.

Schneider, T.D. (2000), Evolution of biological information. Nucleic Acids Research 28: 2794-2799.

Stern, C., 2002. Embryology: Fluid flow and broken symmetry, Nature 418: 29-30.

Thewissen, J. G, M., E. M. Williams, L. J. Roe, and S. T. Hussain, 2001. Skeletons of terrestrial cetaceans and the relationship of whales to artiodactyls, Nature 413: 277-281.

Thewissen, J. G. M., S. T. Hussain, and M. Arif, 1994. Fossil evidence for the origin of aquatic locomotion in archaeocete whales, Science 286: 210-212.

Thornhill, R. H., and D. W. and Ussery, 2000. A classification of possible routes of Darwinian evolution, The Journal of Theoretical Biology 203: 111-116.

Wells, J, 2002. Elusive Icons of Evolution, Natural History 111 (April): 78.

Yonekura, K., S. Maki, D. G. Morgan, D. J. DeRosier, F.Vonderviszt, K.Imada, and K. Namba, 2000. The Bacterial Flagellar Cap as the Rotary Promoter of Flagellin Self-Assembly, Science 290: 2148-2152.